When I read this New York Times piece back in August, I was in the midst of preparation and training for data collection at rural health facilities in Zambia. The Times piece profiles a group called Global Pulse that is doing good work on the 'big data' side of global health:

The efforts by Global Pulse and a growing collection of scientists at universities, companies and nonprofit groups have been given the label “Big Data for development.” It is a field of great opportunity and challenge. The goal, the scientists involved agree, is to bring real-time monitoring and prediction to development and aid programs. Projects and policies, they say, can move faster, adapt to changing circumstances and be more effective, helping to lift more communities out of poverty and even save lives.

Since I was gearing up for 'field work' (more on that here; I'll get to it soon), I was struck at the time by the very different challenges one faces at the other end of the spectrum. Call it small data? And I connected the Global Pulse profile with this, by Wayan Vota, from just a few days before:

The Sneakernet Reality of Big Data in Africa

When I hear people talking about “big data” in the developing world, I always picture the school administrator I met in Tanzania and the reality of sneakernet data transmissions processes.

The school level administrator has more data than he knows what to do with. Years and years of student grades recorded in notebooks – the hand-written on paper kind of notebooks. Each teacher records her student attendance and grades in one notebook, which the principal then records in his notebook. At the local district level, each principal’s notebook is recorded into a master dataset for that area, which is then aggregated at the regional, state, and national level in even more hand-written journals... Finally, it reaches the Minister of Education as a printed-out computer-generated report, complied by ministerial staff from those journals that finally make it to the ministry, and are not destroyed by water, rot, insects, or just plain misplacement or loss. Note that no where along the way is this data digitized and even at the ministerial level, the data isn’t necessarily deeply analyzed or shared widely....

And to be realistic, until countries invest in this basic, unsexy, and often ignored level of infrastructure, we’ll never have “big data” nor Open Data in Tanzania or anywhere else. (Read the rest here.)

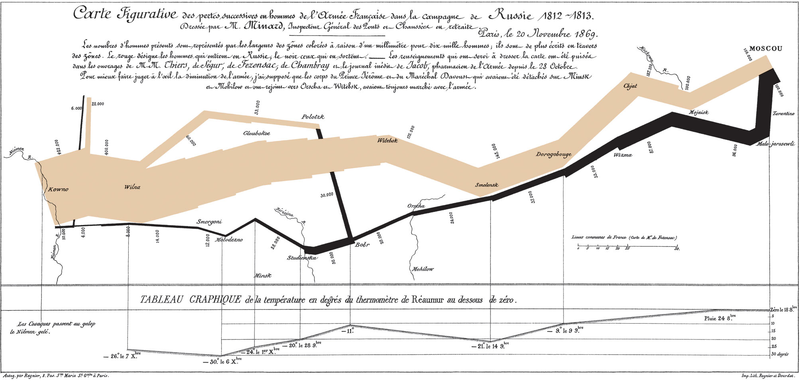

Right on. And sure enough two weeks later I found myself elbow-deep in data that looked like this -- "Sneakernet" in action:

In many countries a quite a lot of data -- of varying quality -- exists, but it's often formatted like the above. Optimistically, it may get used for local decisions, and eventually for high-level policy decisions when it's months or years out of date. There's a lot of hard, good work being done to improve these systems (more often by residents of low-income countries, sometimes by foreigners), but still far too little. This data is certainly primary, in the sense that was collected on individuals, or by facilities, or about communities, but there are huge problems with quality, and with the sneakernet by which it gets back to policymakers, researchers, and (sometimes) citizens.

For the sake of quick reference, I keep a folder on my computer that has -- for each of the countries I work in -- most of the major recent ultimate sources of nationally-representative health data. All too often the only high-quality ultimate source is the most recent Demographic and Health Survey, surely one of the greatest public goods provided by the US government's aid agency. (I think I'm paraphrasing Angus Deaton here, but can't recall the source.) When I spent a summer doing epidemiology research with the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, I was struck by just how many rich data sources there were to draw on, at least compared to low-income countries. Very often there just isn't much primary data on which to build.

On the other end of the spectrum is what you might call the metadata of global health. When I think about the work the folks I know in global health -- classmates, professors, acquaintances, and occasionally thought not often me -- do day to day, much of it is generating metadata. This is research or analysis derived from the primary data, and thus relying on its quality. It's usually smart, almost always well-intentioned, and often well-packaged, but this towering edifice of effort is erected over a foundation of primary data; the metadata sometimes gives the appearance of being primary, when you dig down the sources often point back to those one or three ultimate data sources.

That's not to say that generating this metadata is bad: for instance, modeling impacts of policy decisions given the best available data is still the best way to sift through competing health policy priorities if you want to have the greatest impact. Or a more cynical take: the technocratic nature of global health decision-making requires that we either have this data or, in its absence, impute it. But regardless of the value of certain targeted bits of the metadata, there's the question of the overall balance of investment in primary vs. secondary-to-meta data, and my view -- somewhat ironically derived entirely from anecdotes -- is that we should be investing a lot more in the former.

One way to frame this trade-off is to ask, when considering a research project or academic institute or whatnot, whether the money spent on that project might result in more value for money if it was spent instead training data collectors and statistics offices, or supporting primary data collection (e.g., funding household surveys) in low-income countries. I think in many cases the answer will be clear, perhaps to everyone except those directly generating the metadata.

That does not mean that none of this metadata is worthwhile. On the contrary, some of it is absolutely essential. But a lot isn't, and there are opportunity costs to any investment, a choice between investing in data collection and statistics systems in low-income countries, vs. research projects where most of the money will ultimately stay in high-income countries, and the causal pathway to impact is much less direct.

Looping back to the original link, one way to think of the 'big data' efforts like Global Pulse is that they're not metadata at all, but an attempt to find new sources of primary data. Because there are so few good sources of data that get funded, or that filter through the sneakernet, the hope is that mobile phone usage and search terms and whatnot can be mined to give us entirely new primary data, on which to build new pyramids of metadata, and with which to make policy decisions, skipping the sneakernet altogether. That would be pretty cool if it works out.