It starts with familiar flu-like symptoms: a mild fever, headache, muscle and joint pains. But within days this can quickly descend into something more exotic and frightening: vomiting and diarrhoea, followed by bleeding from the gums, the nose and gastrointestinal tract.

Death comes in the form of either organ failure or low blood pressure caused by the extreme loss of fluids.

Such fear-inducing descriptions have been doing the rounds in the media lately.

However, this is not Ebola but rather Dengue Shock Syndrome, an extreme form of dengue fever, a mosquito-borne disease that struggles to make the news.

That's Seth Berkley, CEO of the GAVI Alliance, writing an opinion piece for the BBC. Berkley argues that Ebola grabs headlines not because it is particularly infectious or deadly, but because those of us from wealthy countries have otherwise forgotten what it's like to be confronted with a disease we do not know how to or cannot afford to treat.

However, in wealthy countries, thanks to the availability of modern medicines, many of these diseases can now usually be treated or cured, and thanks to vaccines they rarely have to be. Because of this blessing we have simply forgotten what it is like to live under threat of such infectious and deadly diseases, and forgotten what it means to fear them.

Ebola does combine infectiousness and rapid lethality, even with treatment, in a way that few diseases do, and it's been uniquely exoticized by books like the Hot Zone. But as Berkley and many others have pointed out, the fear isn't really justified in wealthy countries. They have health systems that can effectively contain Ebola cases if they arrive -- which I'd guess is more likely than not. So please ignore the sensationalism on CNN and elsewhere. (See for example Tara Smith on other cases when hemorraghic fevers were imported into the US and contained.)

But one way that Ebola is different -- in degree if not in kind -- to the other diseases Berkley cites (dengue, measles, childhood diseases) is that its outbreaks are both symptomatic of weak health systems and then extremely destructive to the fragile health systems that were least able to cope with it in the first place.

Like the proverbial canary in the coal mine, an Ebola outbreak reveals underlying weaknesses in health systems. Shelby Grossman highlights this article from Africa Confidential:

MSF set up an emergency clinic in Kailahun [Sierra Leone] in June but several nurses had already died in Kenema. By early July, over a dozen health workers, nurses and drivers in Kenema had contracted Ebola and five nurses had died. They had not been properly equipped with biohazard gear of whole-body suit, a hood with an opening for the eyes, safety goggles, a breathing mask over the mouth and nose, nitrile gloves and rubber boots.

On 21 July, the remaining nurses went on strike. They had been working twelve-hour days, in biohazard suits at high temperatures in a hospital mostly without air conditioning. The government had promised them an extra US$30 a week in danger money but despite complaints, no payment was made. Worse yet, on 17 June, the inexperienced Health and Sanitation Minister, Miatta Kargbo, told Parliament that some of the nurses who had died in Kenema had contracted Ebola through promiscuous sexual activity.

Only one nurse showed up for work on 22 July, we hear, with more than 30 Ebola patients in the hospital. Visitors to the ward reported finding a mess of vomit, splattered blood and urine. Two days later, Khan, who was leading the Ebola fight at the hospital and now with very few nurses, tested positive. The 43-year-old was credited with treating more than 100 patients. He died in Kailahun at the MSF clinic on 29 July...

In addition to the tragic loss of life, there's also the matter of distrust of health facilities that will last long after the epidemic is contained. Here's Adam Nossiter, writing for the NYT on the state of that same hospital in Kenema as of two days ago:

The surviving hospital workers feel the stigma of the hospital acutely.

“Unfortunately, people are not coming, because they are afraid,” said Halimatu Vangahun, the head matron at the hospital and a survivor of the deadly wave that decimated her nursing staff. She knew, all throughout the preceding months, that one of her nurses had died whenever a crowd gathered around her office in the mornings.

There's much to read on the current outbreak -- see also this article by Denise Grady and Sheri Fink (one of my favorite authors) on tracing the index patient (first case) back to a child who died in December 2013. One of the saddest things I've read about previous Ebola outbreaks is this profile of Dr. Matthew Lukwiya, a physician who died fighting Ebola in Uganda.

The current outbreak is different in terms of scale and its having reached urban areas, but if you read through these brief descriptions of past Ebola outbreaks (via Wikipedia) you'll quickly see that the transmission to health workers at hospitals is far too typical. Early transmission seems to be amplified by health facilities that weren't properly equipped to handle the disease. (See also this article article (PDF) on a 1976 outbreak.) The community and the brave health workers responding to the epidemic then pay the price.

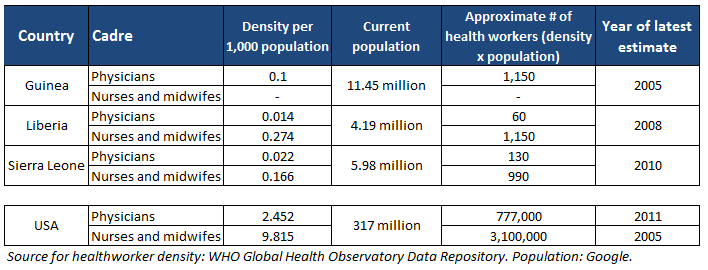

Ebola's toll on health workers is particularly harsh given that the affected countries are starting with an incredible deficit. I was recently looking up WHO statistics on health worker density, and it struck me that the three countries at the center of the current Ebola outbreak are all close to the very bottom of rankings by health worker density. Here's the most recent figures for the ratio of physicians and nurses to the population of each country:*

Liberia has already lost three physicians to Ebola, which is especially tragic given that there are so few Liberian physicians to begin with: somewhere around 60 (in 2008). The equivalent health systems impact in the United States would be something like losing 40,000 physicians in a single outbreak.

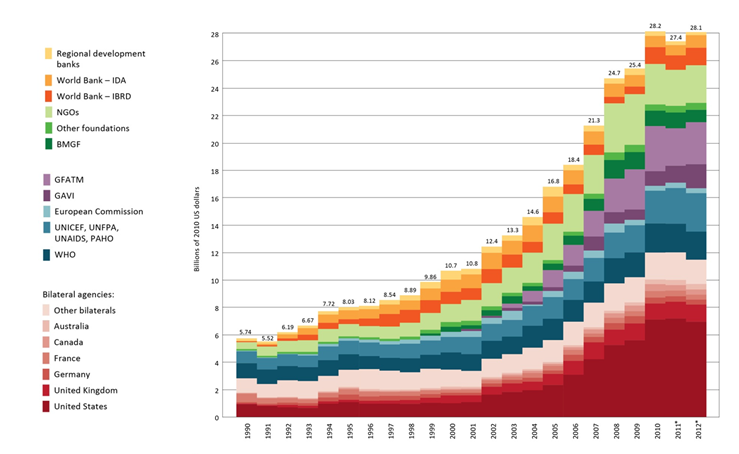

After the initial emergency response subsides -- which will now be on an unprecedented scale and for an unprecedented length of time -- I hope donors will make the massive investments in health worker training and systems strengthening that these countries needed prior to the epidemic. More and better trained and equipped health workers will save lives otherwise lost to all the other infectious diseases Berkley mentioned in the article linked above, but they will also stave off future outbreaks of Ebola or new diseases yet unknown. And greater investments in health systems years ago would have been a much less costly way -- in terms of money and lives -- to limit the damage of the current outbreak.

(*Note on data: this is quick-and-dirty, just to illustrate the scale of the problem. Ie, ideally you'd use more recent data, compare health worker numbers with population numbers from the same year, and note data quality issues surrounding counts of health workers)

(Disclaimer: I've remotely supported some of CHAI's work on health systems in Liberia, but these are my personal views.)