Hopkins: In May I finished final exams for my 4th quarter at Johns Hopkins. That means I'm done with the required four quarters (one year) of coursework towards the MSPH in International Health "Global Disease Epidemiology and Control" (GDEC) track. Looking back I realize that I've learned an incredible amount this year. At some point I hope to write a bit more about the Hopkins experience and major themes in our GDEC coursework, especially for the prospective students who I see end up here through Google searches. The quarter system has pros and cons: it moves fast, which can burn students out by the third or fourth term, but you're also able to shovel a huge dose of knowledge into your brain in a short period of time, leaving the second year of the Masters program more open-ended in comparison to other programs. One reason I chose the MSPH at Hopkins is that flexibility in the second year: you can return and take additional classes after your practicum, or you can spend the entire second year working abroad gaining additional field experience. That flexibility is nice, especially since I'm hoping to work abroad after completing my graduate education and most of my experience in the developing world has been for short periods of time.

In early June I took the comprehensive exams for the MSPH (and hopefully passed!). That means the only requirements I have remaining are a practicum -- 4+ months doing work in international health using the skills I've acquired -- and a Masters paper/thesis based on that practicum. My original plan was to move abroad for a year-long practicum in September, possibly in Nepal, and be done with the MSPH in May of 2012, but that's changed a bit.

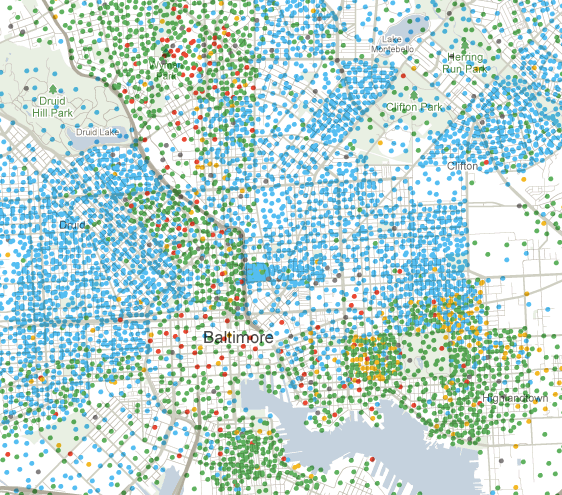

New York: This summer I'm part of the New York City Department of Health's Epi Scholars program. Epi Scholars is a training program that pairs graduate students in epidemiology with researcher mentors in the Department of Health. It's been great so far and I plan to write more about the Department, the training experience, and my particular project -- an in-depth review and analysis of severe lead poisoning cases in New York City in the last 5-10 years. The Epi Scholars program is in its fifth year and has its largest class to date (11 participants this year) so it's been great getting to know the other students as well.

Princeton: This fall I'll be starting work on a Masters of Public Affairs (MPA) at Princeton's Woodrow Wilson School. I'll be doing the Field IV (Economics and Public Policy) concentration at WWS to get their most rigorous training in economics, but I imagine I'll take a number of courses from the Field III (Development Studies) concentration as well. While Hopkins and Princeton don't have an official joint degree program, I've been able to make arrangements to complete both Masters degrees in a total of three years. The right people at both schools have been incredibly supportive of this idea and have helped me work out the details. My timeline will be something like this:

- August 2010 - May 2011 - coursework at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, MD done!

- June - August 2011 - summer internship (NYC Dept of Health Epi Scholars Program) in New York, NY (in progress)

- August 2011 - May 2012 - coursework at the Woodrow Wilson School in Princeton, NJ

- June - December 2012 - practicum work abroad (including writing my Masters thesis for Hopkins), location TBA

- January - May 2013 - back at Princeton for a final semester

The Woodrow Wilson School also gives students the option of taking a "middle year out" if their summer internship is going well or leads naturally to a full-time job. If I went that route I might not finish the MPA until May 2014, but I'd have significantly more work experience when I finally get back on the job market.

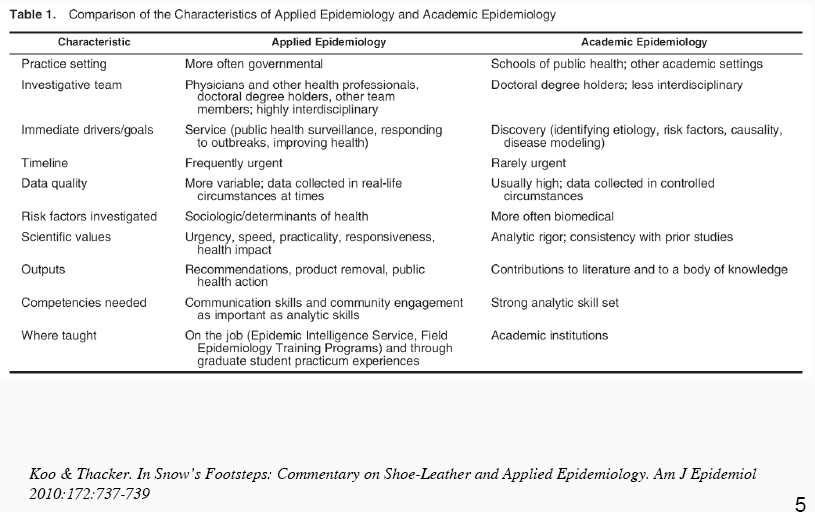

I decided to pursue the dual degree as I realized more and more that my interests -- and the work I want to be prepared to do -- lie at the intersection of global health and economics. I'm interested in the traditional 'applied epidemiology' of studying public health interventions, as well as how those methods are increasingly being used to evaluate development interventions outside of health programs. (Aside: fascinatingly, a recurring critique this year of the development economists conducting RCTs from my public health professors has been that they are much, much too concerned with randomization.) I'm interested in cost-effectiveness evaluations of health and other interventions, and how politics and evidence from various disciplines -- from epidemiology to economics -- get used and misused to make health and development policy.

I'll wrap up the Epi Scholars program here in New York in August in order to move to Princeton by August 20 to start "Math Camp" -- a three week crash course in math and economics to get us all up to speed before real classes start. I've already started to meet some of my incoming WWS classmates as they pass through NYC and I think it will be an amazing experience.