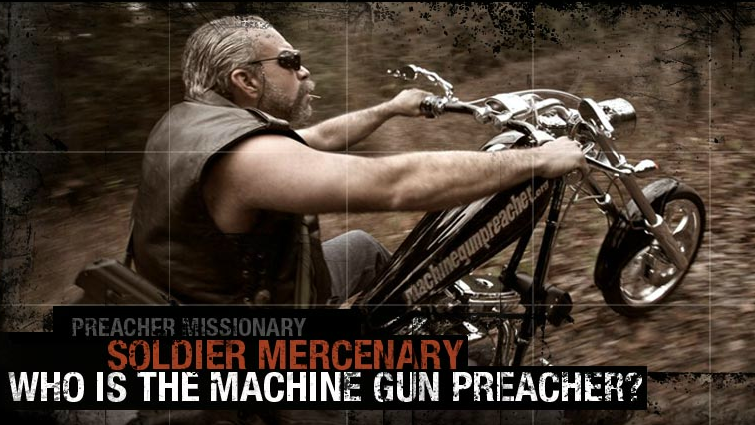

This is part 2 of a longer article on Sam Childers, the “Machine Gun Preacher.” Part 1 is here, or you can read the whole series as one long article. Crush the wicked where they stand

Some of Childers’ most outrageous claims are his most recent. An April 2010 Vanity Fair profile, “Get Kony” by Ian Urbina – worth reading in full – focused on Childers’ personal quest to kill Joseph Kony. Kony is, of course, a really bad guy. He’s the leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a guerilla group in northern Uganda known for its use of child soldiers. Childers claims to be hunting him. Urbina’s story doesn’t present Childers as particularly good at hunting or much closer to catching Kony than any of the others who are out for his head. But the beginning gives you a taste of Childers’ character:

It’s two a.m., and we’re barreling down a deeply pocked dirt road in Southern Sudan. In the cool of night, the temperature is nearly 100 degrees. Sam Childers, 46, is behind the wheel of a chrome-tinted Mitsubishi truck. Christian rock blares on the speakers. He has a Bible on the dash and a shotgun that he calls his “widow-maker” leaning against his left knee. His top sergeant, Santino Deng, 34, a Dinka tribesman with an anthracite complexion and radiant black eyes, sits in the passenger seat, an AK-47 across his lap.

In time, he liquidated his construction business, sold his pit bulls, auctioned his antique-gun collection, and mortgaged his home to help pay for regular trips to Sudan, where he began spending most of his time. He became obsessed with the fate of the thousands of children who have lost their parents to the fighting. In due course he would set up an orphanage in Sudan. But it was Joseph Kony who grabbed his attention. “I found God in 1992,” Childers says, in what is by now a ritual formulation. “I found Satan in 1998.” He has vowed to track Kony down and, in biblical fashion, to smite him.

From there the story gets more elaborate. According to Vanity Fair, Childers claims to be feeding and supplying the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), a southern Sudanese armed group whose political wing has more recently become a major component of independent South Sudan’s government. Childers said that he “made his home in Uganda available to the rebels for a radio-relay station.” He also claims to have been present when the SPLA captured “an L.R.A. soldier believed to be part of Kony’s inner circle. Childers wanted to sedate the man and surgically implant a transmitter so he could be tracked when he returned to the base camp. An S.P.L.A. commander overruled Childers and dealt with the man the old-fashioned way—he executed him.”

No word on whether Childers reported this to anyone before the interview; executing prisoners is a war crime.

God’s RPG stockpile?

The profile continues, describing how a group of soldiers arrive to discuss the hunt for Kony. They ask to see inside his church:

The building, with a high sheet-metal roof and glassless windows, displays no religious markings. Inside, stacked floor to ceiling, sit hundreds of oblong olive-green crates. They contain rocket-propelled grenade launchers, AK-47s, and thousands of rounds of ammunition. The room is dusty, and birds flutter in the rafters. Childers says he supplies mostly the S.P.L.A., and also stores some of its arms. He adds that he has sold weapons to factions in Rwanda and Congo, but declines to specify which ones.

Childers said he gets his weapons from Russians, but only legally. He eventually got frustrated with Urbina’s questions about his arms dealing, but he already admitted a lot. Childers is stockpiling arms, including heavy weapons like RPGs that seem excessive for the needs of an orphanage’s self-protection. He’s storing these weapons in a church at his orphanage (which presumably might make it a target) and he sells weapons to the SPLA, which is not a squeaky clean group. While better than the LRA, the SPLA also has been known to use child soldiers during the period Childers sold them arms. Worse is Childers’ mention of selling weapons to “factions in Rwanda and Congo,” all of which are involved in a convoluted series of conflicts in which all parties have committed terrible crimes. If Childers is truly trying to bring an end to conflict in the region, he should start by recognizing that pumping more small arms into the area isn’t going to help.

In addition to selling arms, Childers claims that his “rescue missions” have also led to his personal engagement in combat. When asked how many LRA members he personally killed, “[Childers] reluctantly admits to ‘more than 10.’” In another long profile – from April 9, 2011 in The Times of London (which I unfortunately can’t find online) Childers appears to say he's only killed in self-defense, though it’s hard to deem armed expeditions to find the LRA “self-defense.” That profile also emphasizes the primacy of Childers’ hunt for Kony. It also describes him showing off the guns he keeps in his bedroom at the orphanage:

He hauls an Uzi machine pistol out of one [plastic crate] and clicks in a 32-round magazine. From another comes a longbarrelled Magnum revolver, and from under his narrow metal-framed bed comes a case containing a Mossberg bolt-action sniper rifle and a pump-action shotgun. Another box beneath the bed is full of hand grenades.

If you’re not convinced already that his tactics are shortsighted and part of the problem, rather than a solution, you might be wondering if – just maybe – Childers knows the local situation so well that he was able to pick the “right” side in the conflict. Other stories indicate that Childers is impatient and interacts poorly with the Sudanese people. Urbina's profile continues (emphasis added):

A little later we pull to the side of the road for firewood to bring back to the orphanage. A woman and her husband stand there with a listless baby who is gravely ill from parasites and malaria. Childers offers to take the woman and child to the hospital in Nimule. The father shyly declines, saying he plans to take her to a different clinic tomorrow. A look of rage flashes in Childers’s eyes. “I ought to beat you right here, you know that?” he yells. “What kind of father are you? You are not serious about your children.” Childers points to a nearby grave, where the family has already buried an infant. “What is wrong with you?” Childers by now is surrounded by several of his soldiers, guns on their shoulders. He steps toward the man. “I should really beat you,” he repeats. Terrified, the father gives in. We take mother and child to the hospital.

The child recovers; Childers almost certainly saved its life. But the bullying lingers in memory long afterward. I remember once asking Childers whether any villagers had ever declined his offer to take their children, or whether he had ever taken any against their will. He erupted angrily: “You know what? I don’t have time to be distracted by this sort of interrogation.”

This is hardly reassuring. While Childers doesn’t answer Urbina’s questions about taking children against their will (or detailed questions about his arms dealing), it’s clear that his own ambitions feed off of media coverage. How else did Urbina come to profile him? Self-aggrandizing is a good word for it. Urbina describes Childers as “droning on about the feature film that he hopes will be made about his life, a project advanced by a Hollywood agent.” Who does that?

Continue reading part 3 here, or you can read the whole series as one long article.