The first question I've had in several recent job interviews/conversations was "do you speak French?" (I don't.) Not that it's impossible to find work if you don't -- but it certainly seems to be a major asset. If you want to work in global health, take note.

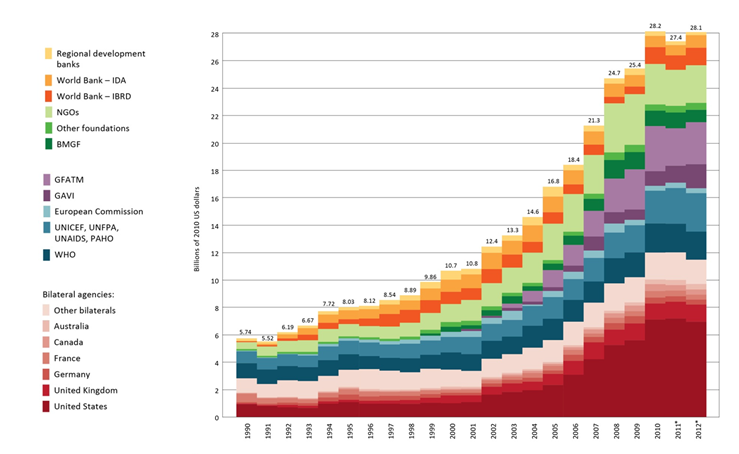

Growth and stagnation in global health funding

Amanda Glassman of CGD shares the graph below from the latest IHME "Financing Global Health" report, which tells the top-line story from the report in one neat picture:

This year's report is subtitled, "The End of the Golden Age?" Maybe. I'd start with Amanda's analysis here, then dive into the report overview [PDF].

Why did HIV decline in Uganda?

That's the title of an October 2012 paper (PDF) by Marcella Alsan and David Cutler, and a longstanding, much-debated question in global health circles . Here's the abstract:

Uganda is widely viewed as a public health success for curtailing its HIV/AIDS epidemic in the early 1990s. To investigate the factors contributing to this decline, we build a model of HIV transmission. Calibration of the model indicates that reduced pre-marital sexual activity among young women was the most important factor in the decline. We next explore what led young women to change their behavior. The period of rapid HIV decline coincided with a dramatic rise in girls' secondary school enrollment. We instrument for this enrollment with distance to school, conditional on a rich set of demographic and locational controls, including distance to market center. We find that girls' enrollment in secondary education significantly increased the likelihood of abstaining from sex. Using a triple-difference estimator, we find that some of the schooling increase among young women was in response to a 1990 affirmative action policy giving women an advantage over men on University applications. Our findings suggest that one-third of the 14 percentage point decline in HIV among young women and approximately one-fifth of the overall HIV decline can be attributed to this gender-targeted education policy.

This paper won't settle the debate over why HIV prevalence declined in Uganda, but I think it's interesting both for its results and the methodology. I particularly like the bit on using distance from schools and from market center in this way, the idea being that they're trying to measure the effect of proximity to schools while controlling for the fact that schools are likely to be closer to the center of town in the first place.

The same paper was previously published as an NBER working paper in 2010, and it looks to me as though the addition of those distance-to-market controls was the main change since then. [Pro nerd tip: to figure out what changed between two PDFs, convert them to Word via pdftoword.com, save the files, and use the 'Compare > two versions of a document' feature in the Review pane in Word.]

Also, a tip of the hat to Chris Blattman, who earlier highlighted Alsan's fascinating paper (PDF) on TseTse flies. I was impressed by the amount of biology in the tsetse fly paper; a level of engagement with non-economic literature that I thought was both welcome and unusual for an economics paper. Then I realized it makes sense given that the author has an MD, an MPH, and a PhD in economics. Now I feel inadequate.

#MiddleEarthPublicHealth

The weekend is almost here, and the new year -- so how to celebrate? For a start, here are the results of a mashup meme I tried to start last night on Twitter: #MiddleEarthPublicHealth: https://storify.com/brettkeller/middleearthpublichealth

If the Storify version (which shows all the tweets) doesn't work, you can search on Twitter for the #MiddleEarthPublicHealth hashtag.

The greatest country in the world

I've been in Ethiopia for six and a half months, and in that time span I have twice found myself explaining the United States' gun culture, lack of reasonable gun control laws, and gun-related political sensitivities to my colleagues and friends in the wake of a horrific mass shooting. When bad things happen in the US -- especially if they're related to some of our national moral failings that grate on me the most, e.g. guns, health care, and militarism -- I feel a sense of personal moral culpability, much stronger when I'm living in the US. I think having to explain how terrible and terribly preventable things could happen in my society, while living somewhere else, makes me feel this way. (This is by no means because people make me feel this way; folks often go out of their way to reassure me that they don't see me as synonymous with such things.)

I think that this enhanced feeling of responsibility is actually a good thing. Why? If being abroad sometimes puts the absurdity of situations at home into starker relief, maybe it will reinforce a drive to change. All Americans should feel some level of culpability for mass shootings, because we have collectively allowed a political system driven by gun fanatics, a media culture unintentionally but consistently glorifying mass murderers, and a horribly deficient mental health system to persist, when their persistence has such appalling consequences.

After the Colorado movie theater shooting I told colleagues here that nothing much would happen, and sadly I was right. This time I said that maybe -- just maybe -- the combination of the timing (immediately post-election) and the fact that the victims were schoolchildren will result in somewhat tighter gun laws. But, attention spans are short so action would need to be taken soon. Hopefully the fact that the WhiteHouse.gov petition on gun control already has 138,000 signatures (making it the most popular petition in the history of the website) indicates that something could well be driven through. Even if that's the case, anything that could be passed now will be just the start and it will be long hard slog to see systematic changes.

As Andrew Gelman notes here, we are all part of the problem to some extent: "It’s a bit sobering, when lamenting problems with the media, to realize that we are the media too." He's talking about bloggers, but I think it extends further: every one of us that talks about gun control in the wake of a mass shooting but quickly lets it slip down our conversational and political priorities once the event fades from memory is part of the problem. I'm making a note to myself to write further about gun control and the epidemiology of violence in the future -- not just today -- because I think that entrenched problems require a conscious choice to break the cycle. In the meantime, Harvard School of Public Health provides some good places to start.

Defaults

Alanna Shaikh took a few thing I said on Twitter and expanded them into this blog post. Basically I was noting -- and she in turn highlighted -- that on matters of paternalism vs. choice, economists' default is consumer choice, whereas the public health default is paternalism. This can and does result in lousy policies from both ends -- for example, see my long critique of Bill Easterly's rejection of effective but mildly paternalistic programs due to (in my view) relying too heavily on the economists' default position.

I was reminder of all this by a recent post on the (awesomely named) Worthwhile Canadian Initiative. The blogger, Frances Wooley, quotes a from a microeconomics textbook: "As a budding economist, you want to avoid lines of reasoning that suggest people habitually do things that make them worse off..." Can you imagine a public health textbook including that sentence? Hah! Wooley, responded, "The problem with this argument is that it flies in the face of the abundant empirical evidence that people habitually overeat, overspend, and do other things that make them worse off."

The historical excesses and abuses of public health are also rooted in this paternalistic streak, just as many of the absurdities of economics are rooted in its own defaults. I think most folks even in these two professions fall somewhere in between these extremes, but that a lot of disagreements (and lack of respect) between the fields stems from this fundamental difference in starting points.

(See also some related thoughts from Terence at Waylaid Dialectic that I saw after writing the initial version of this post.)

On deworming

GiveWell's Alexander Berger just posted a more in-depth blog review of the (hugely impactful) Miguel and Kremer deworming study. Here's some background: the Cochrane review, Givewell's first response to it, and IPA's very critical response. I've been meaning to blog on this since the new Cochrane review came out, but haven't had time to do the subject justice by really digging into all the papers. So I hope you'll forgive me for just sharing the comment I left at the latest GiveWell post, as it's basically what I was going to blog anyway:

Thanks for this interesting review — I especially appreciate that the authors [Miguel and Kremer] shared the material necessary for you [GiveWell] to examine their results in more depth, and that you talk through your thought process.

However, one thing you highlighted in your post on the new Cochrane review that isn’t mentioned here, and which I thought was much more important than the doubts about this Miguel and Kremer study, was that there have been so many other studies that did not find large effect on health outcomes! I’ve been meaning to write a long blog post about this when I really have time to dig into the references, but since I’m mid-thesis I’ll disclaim that this quick comment is based on recollection of the Cochrane review and your and IPA’s previous blog posts, so forgive me if I misremember something.

The Miguel and Kremer study gets a lot of attention in part because it had big effects, and in part because it measured outcomes that many (most?) other deworming studies hadn’t measured — but it’s not as if we believe these outcomes to be completely unrelated. This is a case where what we believe the underlying causal mechanism for the social effects to be is hugely important. For the epidemiologists reading, imagine this as a DAG (a directed acyclic graph) where the mechanism is “deworming -> better health -> better school attendance and cognitive function -> long-term social/economic outcomes.” That’s at least how I assume the mechanism is hypothesized.

So while the other studies don’t measure the social outcomes, it’s harder for me to imagine how deworming could have a very large effect on school and social/economic outcomes without first having an effect on (some) health outcomes — since the social outcomes are ‘downstream’ from the health ones. Maybe different people are assuming that something else is going on — that the health and social outcomes are somehow independent, or that you just can’t measure the health outcomes as easily as the social ones, which seems backwards to me. (To me this was the missing gap in the IPA blog response to GiveWell’s criticism as well.)

So continuing to give so much attention to this study, even if it’s critical, misses what I took to be the biggest takeaway from that review — there have been a bunch of studies that showed only small effects or none at all. They were looking at health outcomes, yes, but those aren’t unrelated to the long-term development, social, and economic effects. You [GiveWell] try to get at the external validity of this study by looking for different size effects in areas with different prevalence, which is good but limited. Ultimately, if you consider all of the studies that looked at various outcomes, I think the most plausible explanation for how you could get huge (social) effects in the Miguel Kremer study while seeing little to no (health) effects in the others is not that the other studies just didn’t measure the social effects, but that the Miguel Kremer study’s external validity is questionable because of its unique study population.

(Emphasis added throughout)

Still #1

Pop quiz: what's the leading killer of children under five? Before I answer, some background: my impression is that many if not most public health students and professionals don't really get politics. And specifically, they don't get how an issue being unsexy or just boring politics can results in lousy public policy. I was discussing this shortcoming recently over dinner in Addis with someone who used to work in public health but wasn't formally trained in it. I observed, and they concurred, that students who go to public health schools (or at least Hopkins, where this shortcoming may be more pronounced) are mostly there to get technical training so that they can work within the public health industry, and that more politically astute students probably go for some other sort of graduate training, rather than concentrating on epidemiology or the like.

The end result is that you get cadres of folks with lots of knowledge about relative disease burden and how to implement disease control programs, but who don't really get why that knowledge isn't acted upon. On the other hand, a lot of the more politically savvy folks who are in a position to, say, set the relative priority of diseases in global health programming -- may not know much about the diseases themselves. Or, maybe more likely, they do the best job they can to get the most money possible for programs that are both good for public health and politically popular. But if not all diseases are equally "popular" this can result in skewed policy priorities.

Now, the answer to that pop quiz: the leading killer of kids under 5 is.... [drumroll]... pneumonia!

If you already knew the answer to that question, I bet you either a) have public health training, or b) learned it due to recent, concerted efforts to raise pneumonia's public profile. On this blog the former is probably true (after all I have a post category called "methodological quibbles"), but today I want to highlight the latter efforts.

To date, most of the political class and policymakers get the pop quiz wrong, and badly so. At Hopkins' school of public health I took and enjoyed Orin Levine's vaccine policy class. (Incidentally, Orin just started a new gig with the Gates Foundation -- congrats!) In that class and elsewhere I've heard Orin tell the story of quizzing folks on Capitol Hill and elsewhere in DC about the top three causes of death for children under five and time and again getting the answer "AIDS, TB and malaria."

Those three diseases likely pop to mind because of the Global Fund, and because a lot of US funding for global health has been directed at them. And, to be fair, they're huge public health problems and the metric of under-five mortality isn't where AIDS hits hardest. But the real answer is pneumonia, diarrhea, and malnutrition. (Or malaria for #3 -- it depends in part on whether you count malnutrition as a separate cause or a contributor to other causes). The end result of this lack of awareness -- and the prior lack of a domestic lobby -- of pneumonia is that it gets underfunded in US global health efforts.

So, how to improve pneumonia's profile? Today, November 12th, is the 4th annual World Pneumonia Day, and I think that's a great start. I'm not normally one to celebrate every national or international "Day" for some causes, but for the aforementioned reasons I think this one is extremely important. You can follow the #WPD2012 hashtag on Twitter, or find other ways to participate on WPD's act page. While they do encourage donations to the GAVI Alliance, you'll notice that most of the actions are centered around raising awareness. I think that makes a lot of sense. In fact, just by reading this blog post you've already participated -- though of course I hope you'll do more.

So, how to improve pneumonia's profile? Today, November 12th, is the 4th annual World Pneumonia Day, and I think that's a great start. I'm not normally one to celebrate every national or international "Day" for some causes, but for the aforementioned reasons I think this one is extremely important. You can follow the #WPD2012 hashtag on Twitter, or find other ways to participate on WPD's act page. While they do encourage donations to the GAVI Alliance, you'll notice that most of the actions are centered around raising awareness. I think that makes a lot of sense. In fact, just by reading this blog post you've already participated -- though of course I hope you'll do more.

I think politically-savvy efforts like World Pneumonia Day are especially important because they bridge a gap between the technical and policy experts. Precisely because so many people on both sides (the somewhat-false-but-still-helpful dichotomy of public health technical experts vs. political operatives) mostly interact with like-minded folks, we badly need campaigns like this to popularize simple facts within policy circles.

If your reaction to this post -- and to another day dedicated to a good cause -- is to feel a bit jaded, please recognize that you and your friends are exactly the sorts of people the World Pneumonia Day organizers are hoping to reach. At the very least, mention pneumonia today on Twitter or Facebook, or with your policy friends the next time health comes up.

---

Full disclosure: while at Hopkins I did a (very small) bit of paid work for IVAC, one of the WPD organizers, re: social media strategies for World Pneumonia Day, but I'm no longer formally involved.

Biological warfare: malaria edition

Did you know Germany used malaria as a biological weapon during World War II? I'm a bit of a WWII history buff, but wasn't aware of this at all until I dove into Richard Evans' excellent three-part history of Nazi Germany, which concludes with The Third Reich at War. Here's an excerpt, with paragraph breaks and some explanations and emphasis added:

Meanwhile, Allied troops continued to fight their way slowly up the [Italian] peninsula. In their path lay the Pontine marshes, which Mussolini had drained at huge expense during the 1930s, converting them into farmland, settling them with 100,000 First World War veterans and their families, and building five new towns and eighteen villages on the site. The Germans determined to return them to their earlier state, to slow the Allied advance and at the same time wreak further revenge on the treacherous [for turning against Mussolini and surrendering to the Allies] Italians.Not long after the Italian surrender, the area was visited by Erich Martini and Ernst Rodenwaldt, two medical specialists in malaria who worked at the Military Medical Academy in Berlin. Both men were backed by Himmler’s Ancestral Heritage research organization in the SS; Martini was on the advisory board of its research institute at Dachau. The two men directed the German army to turn off the pumps that kept the former marshes dry, so that by the end of the winter they were covered in water to a depth of 30 centimetres once more. Then, ignoring the appeals of Italian medical scientists, they put the pumps into reverse, drawing sea-water into the area, and destroyed the tidal gates keeping the sea out at high tide.

On their orders German troops dynamited many of the pumps and carted off the rest to Germany, wrecked the equipment used to keep the drainage channels free of vegetation and mined the area around them, ensuring that the damage they caused would be long-lasting.

The purpose of these measures was above all to reintroduce malaria into the marshes, for Martini himself had discovered in 1931 that only one kind of mosquito could survive and breed equally well in salt, fresh or brackish water, namely anopheles labranchiae, the vector of malaria. As a result of the flooding, the freshwater species of mosquito in the Pontine marshes were destroyed; virtually all of the mosquitoes now breeding furiously in the 98,000 acres of flooded land were carriers of the disease, in contrast to the situation in 1940, when they were on the way to being eradicated.

Just to make sure the disease took hold, Martini and Rodenwaldt’s team had all the available stocks of quinine, the drug used to combat it, confiscated and taken to a secret location in Tuscany, far away from the marshes. In order to minimize the number of eyewitnesses, the Germans had evacuated the entire population of the marshlands, allowing them back only when their work had been completed. With their homes flooded or destroyed, many had to sleep in the open, where they quickly fell victim to the vast swarms of anopheles mosquitoes now breeding in the clogged drainage canals and bomb-craters of the area.

Officially registered cases of malaria spiralled from just over 1,200 in 1943 to nearly 55,000 the following year, and 43,000 in 1945: the true number in the area in 1944 was later reckoned to be nearly double the officially recorded figure. With no quinine available, and medical services in disarray because of the war and the effective collapse of the Italian state, the impoverished inhabitants of the area, now suffering from malnutrition as well because of the destruction of their farmland and food supplies, fell victim to malaria. It had been deliberately reintroduced as an act of biological warfare, directed not only at Allied troops who might pass through the region, but also against the quarter of a million Italians who lived there, people now treated by the Germans no longer as allies but as racial inferiors whose act of treachery in deserting the Axis cause deserved the severest possible punishment.

Obesity pessimism

I posted before on the massive increase in obesity in the US over the last couple decades, trying to understand the why of the phenomenal change for the worse. Seriously, take another look at those maps. A while back Matt Steinglass wrote a depressing piece in The Economist on the likelihood of the US turning this trend around:

I very much doubt America is going to do anything, as a matter of public health policy, that has any appreciable effect on obesity rates in the next couple of decades. It's not that it's impossible for governments to hold down obesity; France, which had rapidly rising childhood obesity early this century, instituted an aggressive set of public-health interventions including school-based food and exercise shifts, nurse assessments of overweight kids, visits to families where overweight kids were identified, and so forth. Their childhood obesity rates stabilised at a fraction of America's. The problem isn't that it's not possible; rather, it's that America is incapable of doing it.

America's national governing ideology is based almost entirely on the assertion of negative rights, with a few exceptions for positive rights and public goods such as universal elementary education, national defence and highways. But it's become increasingly clear over the past decade that the country simply doesn't have the political vocabulary that would allow it to institute effective national programmes to improve eating and exercise habits or culture. A country that can't think of a vision of public life beyond freedom of individual choice, including the individual choice to watch TV and eat a Big Mac, is not going to be able to craft public policies that encourage people to exercise and eat right. We're the fattest country on earth because that's what our political philosophy leads to. We ought to incorporate that into the way we see ourselves; it's certainly the way other countries see us.

On the other hand, it's notable that states where the public has a somewhat broader conception of the public interest, as in the north-east and west, tend to have lower obesity rates.

This reminds me that a classmate asked me a while back about my impression of Michelle Obama's Let's Move campaign. I responded that my impression is positive, and that every little bit helps... but that the scale of the problem is so vast that I find it hard seeing any real, measurable impact from a program like Let's Move. To really turn obesity around we'd need a major rethinking of huge swathes of social and political reality: our massive subsidization of unhealthy foods over healthy ones (through a number of indirect mechanisms), our massive subsidization of unhealthy lifestyles by supporting cars and suburbanization rather than walking and urban density, and so on and so forth. And, as Steinglass notes, the places with the greatest obesity rates are the least likely to implement such change.

Bad pharma

Ben Goldacre, author of the truly excellent Bad Science, has a new book coming out in January, titled Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients. Goldacre published the foreword to the book on his blog here. The point of the book is summed up in one powerful (if long) paragraph. He says this (emphasis added):

So to be clear, this whole book is about meticulously defending every assertion in the paragraph that follows.

Drugs are tested by the people who manufacture them, in poorly designed trials, on hopelessly small numbers of weird, unrepresentative patients, and analysed using techniques which are flawed by design, in such a way that they exaggerate the benefits of treatments. Unsurprisingly, these trials tend to produce results that favour the manufacturer. When trials throw up results that companies don’t like, they are perfectly entitled to hide them from doctors and patients, so we only ever see a distorted picture of any drug’s true effects. Regulators see most of the trial data, but only from early on in its life, and even then they don’t give this data to doctors or patients, or even to other parts of government. This distorted evidence is then communicated and applied in a distorted fashion. In their forty years of practice after leaving medical school, doctors hear about what works through ad hoc oral traditions, from sales reps, colleagues or journals. But those colleagues can be in the pay of drug companies – often undisclosed – and the journals are too. And so are the patient groups. And finally, academic papers, which everyone thinks of as objective, are often covertly planned and written by people who work directly for the companies, without disclosure. Sometimes whole academic journals are even owned outright by one drug company. Aside from all this, for several of the most important and enduring problems in medicine, we have no idea what the best treatment is, because it’s not in anyone’s financial interest to conduct any trials at all. These are ongoing problems, and although people have claimed to fix many of them, for the most part, they have failed; so all these problems persist, but worse than ever, because now people can pretend that everything is fine after all.

If that's not compelling enough already, here's a TED talk on the subject of the new book:

Three new podcasts to follow

- DataStori.es, a podcast on data visualization.

- Pangea, a podcast on foreign affairs -- including "humanitarian issues, health, development, etc." created by Jaclyn Schiff (@J_Schiff).

- Simply Statisics, a podcast by the guys behind the blog of the same name.

Why we should lie about the weather (and maybe more)

Nate Silver (who else?) has written a great piece on weather prediction -- "The Weatherman is Not a Moron" (NYT) -- that covers both the proliferation of data in weather forecasting, and why the quantity of data alone isn't enough. What intrigued me though was a section at the end about how to communicate the inevitable uncertainty in forecasts:

...Unfortunately, this cautious message can be undercut by private-sector forecasters. Catering to the demands of viewers can mean intentionally running the risk of making forecasts less accurate. For many years, the Weather Channel avoided forecasting an exact 50 percent chance of rain, which might seem wishy-washy to consumers. Instead, it rounded up to 60 or down to 40. In what may be the worst-kept secret in the business, numerous commercial weather forecasts are also biased toward forecasting more precipitation than will actually occur. (In the business, this is known as the wet bias.) For years, when the Weather Channel said there was a 20 percent chance of rain, it actually rained only about 5 percent of the time.People don’t mind when a forecaster predicts rain and it turns out to be a nice day. But if it rains when it isn’t supposed to, they curse the weatherman for ruining their picnic. “If the forecast was objective, if it has zero bias in precipitation,” Bruce Rose, a former vice president for the Weather Channel, said, “we’d probably be in trouble.”

My thought when reading this was that there are actually two different reasons why you might want to systematically adjust reported percentages ((ie, fib a bit) when trying to communicate the likelihood of bad weather.

But first, an aside on what public health folks typically talk about when they talk about communicating uncertainty: I've heard a lot (in classes, in blogs, and in Bad Science, for example) about reporting absolute risks rather than relative risks, and about avoiding other ways of communicating risks that generally mislead. What people don't usually discuss is whether the point estimates themselves should ever be adjusted; rather, we concentrate on how to best communicate whatever the actual values are.

Now, back to weather. The first reason you might want to adjust the reported probability of rain is that people are rain averse: they care more strongly about getting rained on when it wasn't predicted than vice versa. It may be perfectly reasonable for people to feel this way, and so why not cater to their desires? This is the reason described in the excerpt from Silver's article above.

Another way to describe this bias is that most people would prefer to minimize Type II Error (false negatives) at the expense of having more Type I error (false positives), at least when it comes to rain. Obviously you could take this too far -- reporting rain every single day would completely eliminate Type II error, but it would also make forecasts worthless. Likewise, with big events like hurricanes the costs of Type I errors (wholesale evacuations, cancelled conventions, etc) become much greater, so this adjustment would be more problematic as the cost of false positives increases. But generally speaking, the so-called "wet bias" of adjusting all rain prediction probabilities upwards might be a good way to increase the general satisfaction of a rain-averse general public.

The second reason one might want to adjust the reported probability of rain -- or some other event -- is that people are generally bad at understanding probabilities. Luckily though, people tend to be bad about estimating probabilities in surprisingly systematic ways! Kahneman's excellent (if too long) book Thinking, Fast and Slow covers this at length. The best summary of these biases that I could find through a quick Google search was from Lee Merkhofer Consulting:

Studies show that people make systematic errors when estimating how likely uncertain events are. As shown in [the graph below], likely outcomes (above 40%) are typically estimated to be less probable than they really are. And, outcomes that are quite unlikely are typically estimated to be more probable than they are. Furthermore, people often behave as if extremely unlikely, but still possible outcomes have no chance whatsoever of occurring.

The graph from that link is a helpful if somewhat stylized visualization of the same biases:

In other words, people think that likely events (in the 30-99% range) are less likely to occur than they are in reality, that unlike events (in the 1-30% range) are more likely to occur than they are in reality, and extremely unlikely events (very close to 0%) won't happen at all.

My recollection is that these biases can be a bit different depending on whether the predicted event is bad (getting hit by lightning) or good (winning the lottery), and that the familiarity of the event also plays a role. Regardless, with something like weather, where most events are within the realm of lived experience and most of the probabilities lie within a reasonable range, the average bias could probably be measured pretty reliably.

So what do we do with this knowledge? Think about it this way: we want to increase the accuracy of communication, but there are two different points in the communications process where you can measure accuracy. You can care about how accurately the information is communicated from the source, or how well the information is received. If you care about the latter, and you know that people have systematic and thus predictable biases in perceiving the probability that something will happen, why not adjust the numbers you communicate so that the message -- as received by the audience -- is accurate?

Now, some made up numbers: Let's say the real chance of rain is 60%, as predicted by the best computer models. You might adjust that up to 70% if that's the reported risk that makes people perceive a 60% objective probability (again, see the graph above). You might then adjust that percentage up to 80% to account for rain aversion/wet bias.

Here I think it's important to distinguish between technical and popular communication channels: if you're sharing raw data about the weather or talking to a group of meteorologists or epidemiologists then you might take one approach, whereas another approach makes sense for communicating with a lay public. For folks who just tune in to the evening news to get tomorrow's weather forecast, you want the message they receive to be as close to reality as possible. If you insist on reporting the 'real' numbers, you actually draw your audience further from understanding reality than if you fudged them a bit.

The major and obvious downside to this approach is that people know this is happening, it won't work, or they'll be mad that you lied -- even though you were only lying to better communicate the truth! One possible way of getting around this is to describe the numbers as something other than percentages; using some made-up index that sounds enough like it to convince the layperson, while also being open to detailed examination by those who are interested.

For instance, we all the heat index and wind chill aren't the same as temperature, but rather represent just how hot or cold the weather actually feels. Likewise, we could report some like "Rain Risk" or "Rain Risk Index" that accounts for known biases in risk perception and rain aversion. The weather man would report a Rain Risk of 80%, while the actual probability of rain is just 60%. This would give us more useful information for the recipients, while also maintaining technical honesty and some level of transparency.

I care a lot more about health than about the weather, but I think predicting rain is a useful device for talking about the same issues of probability perception in health for several reasons. First off, the probabilities in rain forecasting are much more within the realm of human experience than the rare probabilities that come up so often in epidemiology. Secondly, the ethical stakes feel a bit lower when writing about lying about the weather rather than, say, suggesting physicians should systematically mislead their patients, even if the crucial and ultimate aim of the adjustment is to better inform them.

I'm not saying we should walk back all the progress we've made in terms of letting patients and physicians make decisions together, rather than the latter withholding information and paternalistically making decisions for patients based on the physician's preferences rather than the patient's. (That would be silly in part because physicians share their patients' biases.) The idea here is to come up with better measures of uncertainty -- call it adjusted risk or risk indexes or weighted probabilities or whatever -- that help us bypass humans' systematic flaws in understanding uncertainty.

In short: maybe we should lie to better tell the truth. But be honest about it.

Mystification

I read a bunch of articles for my public health coursework, but one that has stuck in my mind and thus been on my things-t0-blog-about list for some time is "Mystification of a simple solution: Oral rehydration therapy in Northeast Brazil" by Marilyn Nations and L.A. Rebhun. Unfortunately I can't find an ungated PDF for it anywhere (aside: how absurd is it that it costs $36 USD to access one article that was published in 1988??) so you can only access it here for free if you have access through a university, etc. The article describes the relatively simple diarrhea treatment, ORT (oral rehydration therapy), as well as how physicians in a rural community in Brazil managed to reclaim this simply procedure and turn it into a highly specialized medical procedure that only they could deliver. One thing I like is that the article has (for an academic piece) a great narrative: you learn how great ORT is ... then about the ridiculous ritualization / mystification of a simple process that keeps it out of reach of those who need it most ... then about the authors' proposed solution ... and finally a twist where you realize the solution has some (though not certainly not all) of the same problems. Here's one of their case studies of how doctors mystified ORT:

Benedita, a 7-month-old girl with explosive, watery diarrhea of 5 days duration, weakness, and marked dehydration, was brought by her mother to a government hospital emergency room. White-garbed nurses and physicians examined the baby and began ORT. They meticulously labeled a sterilized baby bottle with millimeter measurements, weighed the child every lSmin, mixed the chemical packet with clean water, gave the predetermined amount of ORT, and recorded all results on a chart, checking exact times with a wristwatch. The routine continued for over 3 hr, during which little was said to the mother, who waited passively on a wooden bench. Later interviews with the mother revealed that she believed the child’s diarrhea was due to evil eye, and had previously consulted 3 [traditional healers]. Despite her more than 5 hr at the clinic, the mother did not know how to mix the ORT packet herself. When asked if she thought she or a [traditional healer] could mix ORT at home, she replied, “Oh no, we could never do that. It’s so complicated! I don’t even know how to read or write and. I don’t even own a wristwatch!”

They then discuss how they trained a broader group of providers (including the traditional healers) to administer the ORT themselves. But the traditional healers end up ritualizing the treatment as much or more than the physicians did:

... Dona Geralda cradled the leaves carefully so as not to spill their evil content as she carried them to an open window and flung them out. The evil forces causing diarrhea are believed to disappear with the leaves, leaving the child’s body ‘clean’ and disease-free...Turning to the small altar in a comer of the healing room, Dona Geralda offered the ORS 'holy water' to the images of St Francisco and the folk hero Padre Cicero there.

There's more to both sides of the ritualization in the body of the article, and the similarities are striking. I'm not sure the authors intended to make it this way (and this likely speaks more to my own priors or prejudices), but the traditional healers' ritualization sounds quite suspicious to me, full of superstition and empty of understanding of how ORT works, while at the same time the physicians' ritualization, as unnecessary as it is, is comfortingly scientific. The crucial difference though is that the physicians' ritualization seriously impedes access to care, while the healers' process does not -- in fact, it even makes care more accessible:

Clearly, our program did not de-ritualize ORTdelivery; the TH’s administration methods are highly ritualized. The ceremony with the leaves, the prayer,the offering of the ORS-tea to the saints, are all medically unnecessary to ensure the efficacy of ORT.They neither add to nor detract from its technologial effectiveness. But in this case, the ritualization, insteadof discouraging the mother from using ORT and mystifying her about its ease of preparation andadministration, encourages her to participate actively in her child’s cure.

Neat.

mHealth resources

MHealth (ie, mobile health) is all the rage in some public health circles; using mobile technology like phones to collect data, to send reminders for antenatal appointments, etc. I'll be honest that I didn't invest a ton of energy in reading about various mhealth initiatives the last two years while taking classes because a) some of it seems overhyped and b) being a young, tech-savvy health professional I was mildly worried about getting pigeonholed into that work and chose to concentrate more on general methodology and tools. But now that my work involves mhealth (somewhat peripherally for now) I'm paying more attention. Here are two good resources that came across my radar recently:

- William Philbrick of mHealth Alliance has put together a useful report called "mHealth and MNCH: State of the Evidence" (PDF). It summarizes what the research to date on mobile health technology says about maternal, newborn, and child health. Most helpfully, I think, it outlines a few areas where there's not much need for further duplicative research, and other areas where there has been little or no research at all. This is good reading even if you're not particularly interested in mHealth, as the study notes that the mHealth community is fairly close and doesn't always do the best job of disseminating results to the broader global health industry.

- I first saw the link above via my friend and Hopkins classmate Nadi, who sent it out to the mHealth Student Group on Google Groups. Lots of other good links and discussion on that group, so join up!

The longevity transition

Now, the United States and many other countries are experiencing a new kind of demographic transition. Instead of additional years of life being realized early in the lifecycle, they are now being realized late in life. At the beginning of the twentieth century, in the United States and other countries at comparable stages of development, most of the additional years of life were realized in youth and working ages; and less than 20 percent was realized after age 65. Now, more than 75 percent of the gains in life expectancy are realized after 65—and that share is approaching 100 percent asymptotically.... The new demographic transition is a longevity transition: How will individuals and societies respond to mortality decline when almost all of the decline will occur late in life?...

That's from "The New Demographic Transition: Most Gains in Life Expectancy Now Realized Late in Life," (PDF) by Karen Eggleston and Victor Fuchs. Via @KarenGrepin.

A misuse of life expectancy

Jared Diamond is going back and forth with Acemoglu and Robinson over his review of their new book, Why Nations Fail. The exchange is interesting in and of itself, but I wanted to highlight one passage from Diamond's response:

The first point of their four-point letter is that tropical medicine and agricultural science aren’t major factors shaping national differences in prosperity. But the reasons why those are indeed major factors are obvious and well known. Tropical diseases cause a skilled worker, who completes professional training by age thirty, to look forward to, on the average, just ten years of economic productivity in Zambia before dying at an average life span of around forty, but to be economically productive for thirty-five years until retiring at age sixty-five in the US, Europe, and Japan (average life span around eighty). Even while they are still alive, workers in the tropics are often sick and unable to work. Women in the tropics face big obstacles in entering the workforce, because of having to care for their sick babies, or being pregnant with or nursing babies to replace previous babies likely to die or already dead. That’s why economists other than Acemoglu and Robinson do find a significant effect of geographic factors on prosperity today, after properly controlling for the effect of institutions.

I've added the bolding to highlight an interpretation of what life expectancy means that is wrong, but all too common.

It's analagous to something you may have heard about ancient Rome: since life expectancy was somewhere in the 30s, the Romans who lived to be 40 or 50 or 60 were incredibly rare and extraordinary. The problem is that life expectancy -- by which we typically mean life expectancy at birth -- is heavily skewed by infant mortality, or deaths under one year of age. Once you get to age five you're generally out of the woods -- compared to the super-high mortality rates common for infants (less than one year old) and children (less than five years old). While it's true that there were fewer old folks in ancient Roman society, or -- to use Diamond's example -- modern Zambian society, the difference isn't nearly as pronounced as you might think given the differences in life expectancy.

Does this matter? And if so, why? One area where it's clearly important is Diamond's usage in the passage above: examining the impact of changes in life expectancy on economic productivity. Despite the life expectancy at birth of 38 years, a Zambian male who reaches the age of thirty does not just have eight years of life expectancy left -- it's actually 23 years!

Here it's helpful to look at life tables, which show mortality and life expectancy at different intervals throughout the lifespan. This WHO paper by Alan Lopez et al. (PDF) examining mortality between 1990-9 in 191 countries provides some nice data: page 253 is a life table for Zambia in 1999. We see that males have a life expectancy at birth of just 38.01 years, versus 38.96 for females (this was one of the lowest in the world at that time). If you look at that single number you might conclude, like Diamond, that a 30-year old worker only has ~10 years of life left. But the life expectancy for those males remaining alive at age 30 (64.2% of the original birth cohort remains alive at this age) is actually 22.65 years. Similarly, the 18% of Zambians who reach age 65, retirement age in the US, can expect to live an additional 11.8 years, despite already having lived 27 years past the life expectancy at birth.

These numbers are still, of course, dreadful -- there's room for decreasing mortality at all stages of the lifespan. Diamond's correct in the sense that low life expectancy results in a much smaller economically active population. But he's incorrect when he estimates much more drastic reductions in the economically productive years that workers can expect once they reach their economically productive 20s, 30s, and 40s.

----

[Some notes: 1. The figures might be different if you limit it to "skilled workers" who aren't fully trained until age 30, as Diamond does; 2. I'm also assumed that Diamond is working from general life expectancy, which was similar to 40 years total, rather than a particular study that showed 10 years of life expectancy at age 30 for some subset of skilled workers, possibly due to high HIV prevalence -- that seems possible but unlikely; 3. In these Zambia estimates, about 10% of males die before reaching one year of age, or over 17% before reaching five years of age. By contrast, between the ages of 15-20 only 0.6% of surviving males die, and you don't see mortality rates higher than the under-5 ones until above age 85!; and 4. Zambia is an unusual case because much of the poor life expectancy there is due to very high HIV/AIDS prevalence and mortality -- which actually does affect adult mortality rates and not just infant and child mortality rates. Despite this caveat, it's still true that Diamond's interpretation is off. ]

Aid, paternalism, and skepticism

Bill Easterly, the ex-blogger who just can't stop, writes about a conversation he had with GiveWell, a charity reviewer/giving guide that relies heavily on rigorous evidence to pick programs to invest in. I've been meaning to write about GiveWell's approach -- which I generally think is excellent. Easterly, of course, is an aid skeptic in general and a critic of planned, technocratic solutions in particular. Here's an excerpt from his notes on his conversation with GiveWell:

...a lot of things that people think will benefit poor people (such as improved cookstoves to reduce indoor smoke, deworming drugs, bed nets and water purification tablets) {are things} that poor people are unwilling to buy for even a few pennies. The philanthropy community’s answer to this is “we have to give them away for free because otherwise the take-up rates will drop.” The philosophy behind this is that poor people are irrational. That could be the right answer, but I think that we should do more research on the topic. Another explanation is that the people do know what they’re doing and that they rationally do not want what aid givers are offering. This is a message that people in the aid world are not getting.

Later, in the full transcript, he adds this:

We should try harder to figure out why people don’t buy health goods, instead of jumping to the conclusion that they are irrational.

Also:

It's easy to catch people doing irrational things. But it's remarkable how fast and unconsciously people get things right, solving really complex problems at lightning speed.

I'm with Easterly, up to a point: aid and development institutions need much better feedback loops, but are unlikely to develop them for reasons rooted in their nature and funding. The examples of bad aid he cites are often horrendous. But I think this critique is limited, especially on health, where the RCTs and all other sorts of evidence really do show that we can have massive impact -- reducing suffering and death on an epic scale -- with known interventions. [Also, a caution: the notes above are just notes and may have been worded differently if they were a polished, final product -- but I think they're still revealing.]

Elsewhere Easterly has been more positive about the likelihood of benefits from health aid/programs in particular, so I find it quite curious that his examples above of things that poor people don't always price rationally are all health-related. Instead, in the excerpts above he falls back on that great foundational argument of economists: if people are rational, why have all this top-down institutional interference? Well, I couldn't help contrasting that argument with this quote highlighted by another economist, Tyler Cowen, at Marginal Revolution:

Just half of those given a prescription to prevent heart disease actually adhere to refilling their medications, researchers find in the Journal of American Medicine. That lack of compliance, they estimate, results in 113,00 deaths annually.

Let that sink in for a moment. Residents of a wealthy country, the United States, do something very, very stupid. All of the RCTs show that taking these medicines will make them live longer, but people fail to overcome the barriers at hand to take something that is proven to make them live longer. As a consequence they die by the hundreds of thousands every single year. Humans may make remarkably fast unconscious decisions correctly in some spheres, sure, but it's hard to look at this result and see any way in which it makes much sense.

Now think about inserting Easterly's argument against paternalism (he doesn't specifically call it that here, but has done so elsewhere) in philanthropy here: if people in the US really want to live, why don't they take these medicines? Who are we to say they're irrational? That's one answer, but maybe we don't understand their preferences and should avoid top-down solutions until we have more research.

A reductio ad absurdum? Maybe. On the one hand, we do need more research on many things, including medication up-take in high- and low-income countries. On the other hand, aid skepticism that goes far enough to be against proven health interventions just because people don't always value those interventions rationally seems to line up a good deal with the sort of anti-paternalism-above-all streak in conservatism that opposes government intervention in pretty much every area. Maybe it's a good policy to try out some nudge-y (libertarian paternalism, if you will) policies to encourage people to take their medicine, or require people to have health insurance they would not choose to buy on their own.

Do you want to live longer? I bet you do, and it's safe to assume that people in low-income countries do as well. Do you always do exactly what will help you do so? Of course not: observe the obesity pandemic. Do poor people really want to suffer from worms or have their children die from diarrhea? Again, of course not. While poor people in low-income countries aren't always willing to invest a lot of time or pay a lot of money for things that would clearly help them stay alive for longer, that shouldn't be surprising to us. Why? Because the exact same thing is true of rich people in wealthy countries.

People everywhere -- rich and poor -- make dumb decisions all the time, often because those decisions are easier in the moment due to our many irrational cognitive and behavioral tics. Those seemingly dumb decisions usually reveal the non-optimal decision-making environments in which we live, but you still think we could overcome those things to choose interventions that are very clearly beneficial. But we don't always. The result is that sometimes people in low-income countries might not pay out of pocket for deworming medicine or bednets, and sometimes people in high-income countries don't take their medicine -- these are different sides of the same coin.

Now, to a more general discussion of aid skepticism: I agree with Easterly (in the same post) that aid skeptics are a "feature of the system" that ultimately make it more robust. But it's an iterative process that is often frustrating in the moment for those who are implementing or advocating for specific programs (in my case, health) because we see the skeptics as going too far. I'm probably one of the more skeptical implementers out there -- I think the majority of aid programs probably do more harm than good, and chose to work in health in part because I think that is less true in this sector than in others. I like to think that I apply just the right dose of skepticism to aid skepticism itself, wringing out a bit of cynicism to leave the practical core.

I also think that there are clear wins, supported by the evidence, especially in health, and thus that Easterly goes too far here. Why does he? Because his aid skepticism isn't simply pragmatic, but also rooted in an ideological opposition to all top-down programs. That's a nice way to put it, one that I think he might even agree with. But ultimately that leads to a place where you end up lumping things together that are not the same, and I'll argue that that does some harm. Here are two examples of aid, both more or less from Easterly's post:

- Giving away medicines or bednets free, because otherwise people don't choose to invest in them; and,

- A World Bank project in Uganda that "ended up burning down farmers’ homes and crops and driving the farmers off the land."

These are a both, in one sense, paternalistic, top-down programs, because they are based on the assumption that sometimes people don't choose to do what is best for themselves. But are they the same otherwise? I'd argue no. One might argue that they come from the same place, and an institution that funds the first will inevitably mess up and do the latter -- but I don't buy that strong form of aid skepticism. And being able to lump the apparently good program and the obviously bad together is what makes Easterly's rhetorical stance powerful.

If you so desire, you could label these two approaches as weak coercion and strong coercion. They are both coercive in the sense that they reshape the situations in which people live to help achieve an outcome that someone -- a planner, if you will -- has decided is better. All philanthropy and much public policy is coercive in this sense, and those who are ideologically opposed to it have a hard time seeing the difference. But to many of us, it's really only the latter, obvious harm that we dislike, whereas free medicines don't seem all that bad. I think that's why aid skeptics like Easterly group these two together, because they know we'll be repulsed by the strong form. But when they argue that all these policies are ultimately the same because they ignore people's preferences (as demonstrated by their willingness to pay for health goods, for example), the argument doesn't sit right with a broader audience. And then ultimately it gets ignored, because these things only really look the same if you look at them through certain ideological lenses.

That's why I wish Easterly would take a more pragmatic approach to aid skepticism; such a form might harp on the truly coercive aspects without lumping them in with the mildly paternalistic. Condemning the truly bad things is very necessary, and folks "on the inside' of the aid-industrial complex aren't generally well-positioned to make those arguments publicly. However, I think people sometimes need a bit of the latter policies, the mildly paternalistic ones like giving away medicines and nudging people's behavior -- in high- and low-income countries alike. Why? Because we're generally the same everywhere, doing what's easiest in a given situation rather than what we might choose were the circumstances different. Having skeptics on the outside where they can rail against wrongs is incredibly important, but they must also be careful to yell at the right things lest they be ignored altogether by those who don't share their ideological priors.

Mimicking success

If you don't know what works, there can be an understandable temptation to try to create a picture that more closely resembles things that work. In some of his presentations on the dire state of student learning around the world, Lant Pritchett invokes the zoological concept of isomorphic mimicry: the adoption of the camouflage of organizational forms that are successful elsewhere to hide their actual dysfunction. (Think, for example, of a harmless snake that has the same size and coloring as a very venomous snake -- potential predators might not be able to tell the difference, and so they assume both have the same deadly qualities.) For our illustrative purposes here, this could mean in practice that some leaders believe that, since good schools in advanced countries have lots of computers, it will follow that, if computers are put into poor schools, they will look more like the good schools. The hope is that, in the process, the poor schools will somehow (magically?) become good, or at least better than they previously were. Such inclinations can nicely complement the "edifice complex" of certain political leaders who wish to leave a lasting, tangible, physical legacy of their benevolent rule. Where this once meant a gleaming monument soaring towards the heavens, in the 21st century this can mean rows of shiny new computers in shiny new computer classrooms.

That's from this EduTech post by Michael Trucano. It's about the recent evaluations showing no impact from the One Laptop per Child (OLPC) program, but I think the broader idea can be applied to health programs as well. For a moment let's apply it to interventions designed to prevent maternal mortality. Maternal mortality is notoriously hard to measure because it is -- in the statistical sense -- quite rare. While many 'rates' (which are often not actual rates, but that's another story) in public health are expressed with denominators of 1,000 (live births, for example), maternal mortality uses a denominator of 100,000 to make the numerators a similar order of magnitude.

That means that you can rarely measure maternal mortality directly -- even with huge sample sizes you get massive confidence intervals that make it difficult to say whether things are getting worse, staying the same, or improving. Instead we typically measure indirect things, like the coverage of interventions that have been shown (in more rigorous studies) to reduce maternal morbidity or mortality. And sometimes we measure health systems things that have been shown to affect coverage of interventions... and so forth. The worry is that at some point you're measuring the sort of things that can be improved -- at least superficially -- without having any real impact.

All that to say: 1) it's important to measure the right thing, 2) determining what that 'right thing' is will always be difficult, and 3) it's good to step back every now and then and think about whether the thing you're funding or promoting or evaluating is really the thing you care about or if you're just measuring "organizational forms" that camouflage the thing you care about.

(Recent blog coverage of the OLPC evaluations here and here.)

Where are the programs?

An excerpt from Bill Gates' interview with Katherine Boo, author of Behind the Beautiful Forevers (about a slum in Mumbai):

Bill Gates: Your peek into the operations of some non-profits was concerning. Are there non-profits that have been doing work which actually contributes to the improvement of these environments? Katherine Boo: There are many nonprofits doing work that betters lives and prospects in India, from SEWA to Deworm the World, but in the airport slums, the closer I looked at NGOs, the more disheartened I felt. WorldVision, the prominent Christian charity, had made major improvements to sanitation some years back, but mismanagement and petty corruption in the organization's local office had hampered more recent efforts to distribute aid. Other NGOs were supposedly running infant-health programs and schools for child laborers, but that desperately needed aid existed only on paper. Microfinance groups were reconfigured to exploit the very poor. Annawadi residents dying of untreated TB, malaria and dengue fever were nominally served by many charitable organizations, but in reality encountered only a single strain of health advocate—from the polio mop-up campaign. (To Annawadians, the constant appearance of polio teams in slum lanes being eviscerated by other illnesses has become a local joke.) I tend to be realistic about occasional failures and "leakages" in organizations that do ambitious work in difficult contexts, but the discrepancy between what many NGOs were claiming in fundraising materials and what they were actually doing was significant.In general, I suspect that the reading public overestimates the penetration of effective NGOs in low-income communities--a misapprehension that we journalists help create. When writing about nonprofits, we tend to focus either on scandals or on thinly reported "success stories" that, en masse, create the impression that most of the world's poor are being guided through life by nigh-heroic charitable assistance. It'd be cool to see that misperception become more of a reality in the lives of low-income families.