The news out of Joplin, Missouri is heartbreaking, and it comes so quickly on the heels of the tornadoes that hit Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Central Arkansas, where I grew up, gets hit by tornadoes every spring, so I have plenty of memories of taking shelter in response to warnings. College nights with social plans ruined when we had to hunker down in an interior hallways. Dark, roiling clouds circling and the spooky calm when the rain and hail stop but the winds stay strong. Racing home from work to get to my house and its basement -- a rarity in the South -- before a particularly ominous storm hit. Neighboring communities were sometimes hit more directly by storms, and Harding students often participated in clean-up an recovering efforts, but my town was spared direct hits by the heaviest tornadoes.

So what does epidemiology have to say about tornadoes? Their paths aren't exactly random, in the sense that some areas are more prone to storms that produce tornadoes. Growing up I knew where to take shelter: interior hallways away from windows if your house didn't have a basement or a dedicated storm shelter. I also knew that mobile homes were a particularly bad place to be, and that the carnage was always worst when a tornado happened to hit a mobile home lot.

But there is some interesting research out there that tells us more than you might think. Obviously and thankfully you can't do a randomized trial assigning some communities to get storms and others not, so the evidence of how to prevent tornado-related injury and death is mostly observational. What do we know? I'm not an expert on this but I did a quick, non-systematic scan and here's what I found:

First, the annual tornado mortality rate has actually gone down quite a lot over the last few decades. That says nothing about the frequency and intensity of tornadoes themselves, which is a matter for meteorologists to research. The actual number deaths resulting from tornadoes would probably be a function of the number of people in the US, where they live and whether those areas are prone to tornadoes, the frequency and intensity of the tornadoes, and risk factors for people in the affected area once the tornado hits.

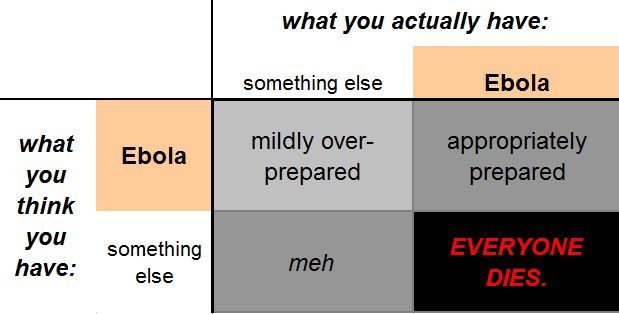

This NOAA site has the following graph of tornado mortality where the vertical axis is tornado deaths per million people in the US (on a log scale) and the horizontal axis covers 1875 - 2008.

Second, many of the risk factors for tornado injury and death are intuitive and suggest possible interventions to minimize risk in tornado-prone areas. Following tornadoes in North and South Carolina in 1984, Eidson et al. surveyed people hospitalized and family members of people who were killed, along with uninjured persons who were present when the surveyed individuals were hurt. The main types of injury were deep cuts, concussions, unconsciousness and broken bones. Risk factors included living in mobile homes, "advanced age (60+ years), no physical protection (not having been covered with a blanket or other object), having been struck by broken window glass or other falling objects, home lifted off its foundation, collapsed ceiling or floor, or walls blown away." Some of those patterns might indicate potential tornado education interventions -- better shelters for mobile home residents, targeting alerts to older residents, covering with a blanket, and staying in interior hallways, to say nothing of building codes to make more survivable structures.

Third, some things are less clear, like whether it's safe to be in a car during a tornado. Daley et al. did a case-control study of tornado injuries and deaths in the aftermath of tornadoes in Oklahoma in 1999. They found higher risk of tornado death for those in mobile homes (odds ratio of 35.3, 95% CI 7.8 - 175.6) or outdoors (odds ratio of 141.2, 95% CI 15.9 - a whopping 6,379.8) compared to other houses. They found no difference in risk of death, severe injury, or minor injury among people in cars vs. those in houses. And they found that risk of death, severe injury, or minor injury was actually lower among those "fleeing their homes in motor vehicles than among those remaining." That's surprising to me, and contrary to much of the tornado-related safety warnings I heard from meteorologists and family growing up. I wonder if this particular study goes against the majority of findings, or whether there is a consensus based in data at all.

Fourth, our knowledge of tornadoes can be messy. One demographic approach to tornado risk factors (Donner 2007) is to look for correlations between tornado fatalities and injuries with rural population, population density, household size, racial minorities, deprivation/poverty, tornado watches and warnings, and mobile homes. Donner noted that "Findings suggest a strong relationship between the size of a tornado path and both fatalities and injuries, whereas other measures related to technology, population, and organization produce significant yet mixed results."

That's just a sampling of the literature on tornado epidemiology. The studies are interesting but relatively rare, at least from initial perusal. That's probably because tornado deaths and injuries are relatively rare in the US. Still, the storms themselves are terrifying and they often wreak havoc on a single community and thus generate more sympathy and news coverage than a more frequent -- and thus less extraordinary -- problem like car crashes.

Update: NYT has an interesting article about tornado preparedness, including some speculation on why the Joplin tornado was so bad.